This article was originally published in the Winter 2012 edition of Newsline.

The World Health Organisation has identified antimicrobial resistance as one of the three greatest threats to human health. Although it has been an issue for a long time now, what has been done to address this? Infection control programs have been very successful in controlling the prevalence of infections caused by multi-resistant organisms, but it is now time to face the problem head on and try to prevent or stop the emergence of these so-called ‘super bugs.’

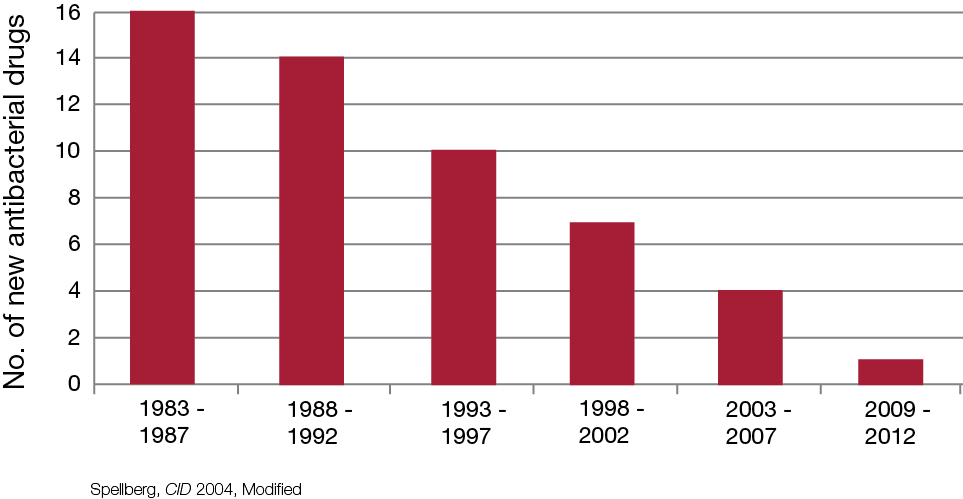

For the past 20 years, the number of new antimicrobial agents approved by the FDA have decreased significantly as seen in Table 1. The Infectious Disease Society of America has launched a collaboration titled the 10 x ‘20 Initiative, which is aimed at stimulating new research into developing at least 10 new, safe, and effective antimicrobials by 2020. Although this initiative has been backed by key global leaders including US President, Barack Obama, joined with Swedish Prime Minister, Fredrik Reinfeldt, on behalf of the European Union, there still appears to be some struggle in convincing drug companies to invest in this area. The development of new antimicrobials usually takes an average of 8 years from laboratory to market at a cost of around US$800,000,000. Aside from this, new antimicrobials are usually only used for short courses, are usually restricted/regulated due to the cost, and resistance seems to be inevitable. Once resistance develops, the usage of the drug would most definitely be affected. Drug companies tend to find other markets like chronic disease and lifestyle drugs more attractive as the market is more predictable and stable.

Table 1. Antibacterial Approvals.*

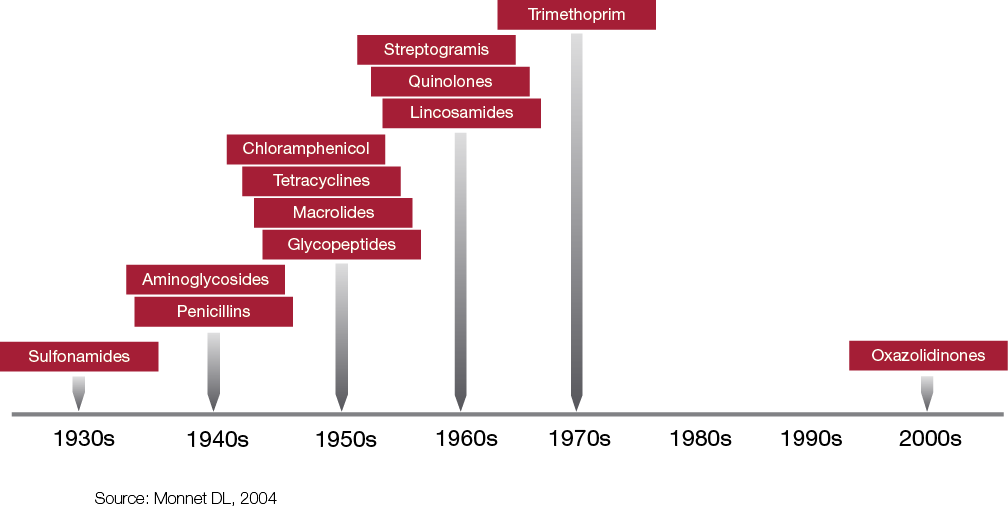

Table 2. The development of new antibacterial drug classes.*

The first truly effective antibacterial agent, sulfanilamide, gave humanity an advantage in our struggle against microorganisms, even saving Winston Churchill’s life during the Second World War! If, however, the current rate of emerging resistance to antimicrobial agents continues, coupled with the decline in the development of new agents, it is possible that we may enter into what some have termed the ‘post antibiotic era.’ A case was reported in the MJA in 2010 by A. Geethanie et al. where a man in his mid 50’s came back from India after elective surgery and was found to have a strain of Providencia rettgeri producing the New Delhi metallo-ß-lactamase, the first case in Australia. The isolate was resistant to all ß-lactam antibiotics, including meropenem, as well as to all aminoglycosides, ciprofloxacin, tigecycline and colistin. If the patient had developed a serious infection with this organism there may have been no antibiotic available to treat it, along with the risk of cross-infection within healthcare facilities.

The relationship between antibiotic use and resistance is complicated. It has been shown that the incidence of resistance correlates with the increase in prescribing of antibiotics but there is little data to suggest that a decrease actually results in a decrease in the incidence of resistance to a specific antibiotic. S. Harbarth et al. actually found that there is a lower risk of vancomycin-resistant enterococci associated with intravenous vancomycin use, instead, agents such as broad-spectrum cephalosporins and clindamycin appeared to increase the risk of isolating vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Preventing the emergence of resistant strains does not just involve reducing antimicrobial prescribing, rather we should be looking at prescribing antimicrobials more efficiently; some common strategies include guideline-based prescribing, optimising the dose, timing, and duration of antimicrobials and implementing Antimicrobial Stewardship programs.

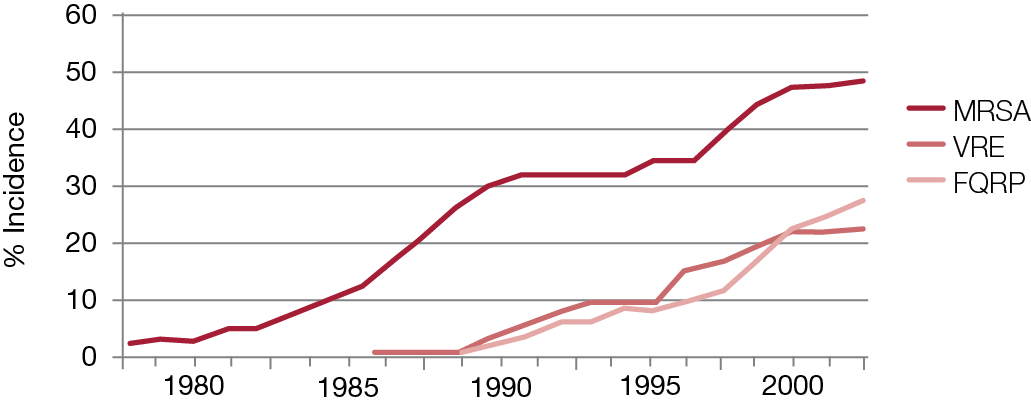

Table 3. The incidence of new antibacterial drug classes.*

Studies have shown that up to 50% of antibiotic regimens prescribed in Australian hospitals are inappropriate. Antimicrobial Stewardship is defined as ‘an ongoing effort by a healthcare institution to optimise antimicrobial use among hospital patients in order to improve patient outcomes, ensure cost-effective therapy and reduce adverse sequelae of antimicrobial use (including antimicrobial resistance)’. The Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America have found that an efficient Antimicrobial Stewardship program has the ability to improve appropriate antimicrobial use; decrease total antimicrobial drug use (22–36%), decrease institutional resistance rates, decrease healthcare costs, and most importantly decrease treatment failures, mortality and length of stay.

A good Antimicrobial Stewardship program does not just involve setting up guidelines and restrictions on antimicrobial drug use; according to M. Hulscher et al. ‘changing hospital antibiotic use is a challenge of formidable complexity’. The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare’s Antimicrobial Stewardship Advisory Committee has released a publication on the role of these programs which includes recommendations and strategies on how to implement an effective program. Pharmacists can play a key role in implementing an effective Antimicrobial Stewardship program. Experience from the Royal Perth Hospital’s Antimicrobial Stewardship Committee even suggests that employing an Infectious Disease Pharmacist actually pays for itself in drug cost savings alone and at the same time having safety and quality benefits at no extra cost. Pharmacists are in a position to participate and make positive contributions in the governance of antimicrobials. We also have the means and resources to monitor and report usage data, conduct Drug Usage Evaluations and Quality Use of Medicine indicator monitoring.

The challenges posed by infections caused by multi-resistant organisms continue to escalate, causing patient morbidity, mortality and increasing healthcare costs. A 2005 report from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that mortality rate caused by MRSA infections has already overtaken that caused by HIV/AIDS and would continue to increase unless healthcare institutions take steps to limit its spread.

Pharmacists are tasked as members of the healthcare team to ensure that medications are used appropriately. The core principles of Quality Use of Medicine align with the main objectives of Antimicrobial Stewardship, making sure we optimise the use of antibiotics. A simple query on treatment duration could prompt the busy physician to review the appropriateness of a regimen and may result in cessation of unnecessary doses. This simple intervention can have immediate impact on decreasing healthcare costs, and also decreasing the potential of developing adverse effects, and selective pressure towards resistant organisms.

Please ask your pharmacist regarding a range of services HPS Pharmacies could provide regarding Antimicrobial Stewardship for your hospital or health facility.

*Tables reproduced with permission from R Guidos. Infectious Diseases Society of America.

References:

- Buising K. Antimicrobial Stewardship Where’s the Evidence? Proceedings of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Forum, Royal Melbourne Hospital: 2010, Melbourne, Victoria.

- Buising K, Duguid MJ. Antimicrobial Stewardship. Proceedings of the 36th National Conference of the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia: 2010 Nov 11–14, Melbourne, Victoria.

- Coombes JA, Whitby RM, Radford JM, Looke DF. Vancomycin usage review in the era of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). Aust J Hosp Pharm 1997. 27(2): 140–3.

- Cruickshank M., Duguid M, (eds). Antimicrobial stewardship in Australian Hospitals. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2010.

- Dellit T, Owens R, McGowan J Jr, Gerding D, Weinstein R, Burke J et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Guidelines for Developing an Institutional Program to Enhance Antimicrobial Stewardship. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44(2): 159–77.

- Fernando GATP, Collignon PJ, Bell JM. A risk for returned travellers: the “post-antibiotic era” [letter]. Med J Australia 2010; 193(1): 59.

- Guidos R. Bad Bugs, No Drugs / Strategies to Address Antimicrobial resistance (STAAR) Our Advocacy Campaign. Proceedings of the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists Annual Meeting; 2008 Oct 24; Washington DC.

- Gwynne P, Heebner G. Laboratory Technology Trends: Drug Discovery: 5. Science 2002. Available from www.sciencemag.org/site/products/dd5_11_01_02.xhtml. Accessed 5 June 2012.

- Harbarth S, Cosgrove S, Carmeli Y. Effects of antibiotics on nosocomial epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2002 Jun; 46(6): 1619–28.

- Infectious Diseases Society of America. Bad bugs, no drugs: as antibiotic discovery stagnates, a public health crisis brews. Alexandria, VA: Infectious Diseases Society of America; 2004.

- MacDougall C, Polk R. Antimicrobial stewardship program in health care systems. Clin Microbial Rev 2005; 18(4): 638–56.

- Radford J, Cardiff L, Pillans P, Fielding D, Looke D. Drug usage evaluation of antimicrobial therapy for community-acquired pneumonia. Aust J Hosp Pharm 1999; 29(6): 314–320.

- Robertson M, Dartnell J, Korman T, Ioannides-Demos L, Kirsa S, Lord J et al. Ceftriaxone and cefotaxime use in Victorian Hospitals. Med J Aust 2002 176(11): 524–529.

- Rawlins MD, Murray RJ, Van Gessel H, et al. Review of the first six months of an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) in a WA teaching hospital. Proceedings of Antimicrobials 2005; 2005 Feb 24–26. Lorne, Victoria.