Clozapine is an antipsychotic medication that was pioneered in 1959 and introduced to clinical practice in the 1970s. It remains the gold standard for treatment–resistant schizophrenia, although a recent meta-analysis suggests that there is insufficient evidence to prove its superiority over other atypical antipsychotics. In addition to its use as an antipsychotic, clozapine also exhibits anti-suicidal and anti-aggressive properties and is effective in the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder that is resistant to conventional therapy. Although clozapine has an important place in psychiatry, it does come with a variety of side effects. Some of these side effects are potentially fatal; the most prominent among them being neutropenia and agranulocytosis. Neutropenia has been reported to occur in 2% to 3% of patients and agranulocytosis in 1% of patients. Consequently, patients taking clozapine require baseline white blood cell counts and must maintain results within normal parameters for the duration of therapy.

The optimal use of clozapine may be compromised by other significant side effects, including diabetes mellitus, weight gain, metabolic syndrome, myocarditis, and gastrointestinal conditions. Most of these side effects are not exclusive to clozapine and can be observed in other second–generation antipsychotics. Many of the other side effects associated with clozapine use may not be considered as important as they do not present an immediate danger to the patient. However, these effects can be troublesome and may impact on patient quality of life, leading to emotional distress and treatment cessation.

There are approaches available to help alleviate many of the troublesome side effects of clozapine. Therefore, it is highly likely that termination of treatment is unwarranted in many cases. Failure to address these side effects may lead to unnecessary discontinuation of clozapine, thus depriving patients of what could be the only effective intervention for them. This article will focus on some practical strategies to manage two gastrointestinal side effects of clozapine that are commonly overlooked: hypersalivation and constipation.

Hypersalivation (Sialorrhea)

Clozapine–induced hypersalivation occurs very commonly, with reported incidences ranging from 30% to 80%. This effect typically commences at the onset of treatment and can diminish with time. However, it may be severe and persistent. It is typically more problematic at night while sleeping, and patients may complain of wet pillows or feeling suffocated as saliva accumulates near the vocal cords. Furthermore, wet clothing and unpleasant odour can be a consequence of excessive drooling. The psychosocial difficulties associated with this issue may result in non-compliance and self–cessation of clozapine treatment. Hypersalivation may also contribute to the development of aspiration pneumonia, which can lead to serious complications.

Saliva production is primarily regulated by the parasympathetic system; M3 muscarinic receptors in particular. Stimulation of this system promotes the production of high volume, low protein saliva. Saliva production is also controlled to a lesser degree by the sympathetic system which promotes low volume, high protein saliva. Clozapine displays an antagonistic effect at M1, M2, M3 and M5 muscarinic receptors, so it could be expected to reduce saliva production. The paradoxical increase in saliva production may be explained by the partial agonist activity of clozapine at M4 receptors and antagonist activity at autoinhibitory α2 adrenergic receptors. Oesophageal motility may also be reduced by clozapine, enhancing the appearance of hypersalivation due to the impairment of normal salivary clearance.

There are various pharmacological and non–pharmacological strategies that can be implemented to provide relief of clozapine–induced hypersalivation. However, it is essential to educate patients about this common side effect when commencing treatment. Some strategies are listed below.

Non–pharmacological approaches:

- Chewing gum may help as it promotes swallowing

- Elevating the head with extra pillows while sleeping

- Maintaining lateral decubitus position at night

- Placing a towel on the pillow to absorb excess saliva at night

Pharmacological treatment options:

- Clinicians may consider a dose reduction

- Anticholinergic medications, such as atropine, may be administered sublingually (ophthalmologic preparations may need to be used due to a lack of proprietary products)

- α2 agonists, such as clonidine, may be administered orally

There are currently no unequivocal guidelines for the proper treatment of hypersalivation associated with clozapine pharmacotherapy due to a scarcity of high-quality research and a lack of licensed pharmacological treatment options. A 2013 case study by Mustafa et al. demonstrated that significant symptom relief may be obtained with the combination of atropine drops and hyoscine tablets.

Constipation

Constipation is a very common side effect experienced by patients taking clozapine. The occurrence of constipation has been reported to be 33.3% during acute treatment and 22.8% during maintenance treatment. It has been recognised that there is an association between constipation and the potent anticholinergic activity of clozapine. This anticholinergic activity contributes to other gastrointestinal motility problems, including delayed gastric emptying that can lead to nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Clozapine also displays antiserotonergic activity that may contribute to additional gastrointestinal side effects. The mechanism of clozapine–induced constipation is, therefore, considered to be multifactorial.

It is important to recognise that constipation is associated with serious complications, such as faecal impaction, bowel obstruction and perforation, paralytic ileus, gastrointestinal ischemia and even death. A high–fibre diet, plenty of fluid and exercise should be recommended to patients. However, these non–pharmacological approaches tend to be ineffective in clozapine–induced constipation. The use of stool softeners and laxatives are frequently used. Unfortunately, chronic constipation may persist throughout clozapine therapy. The safety of long-term stimulant laxative use is still controversial due to the risk of cathartic colon.

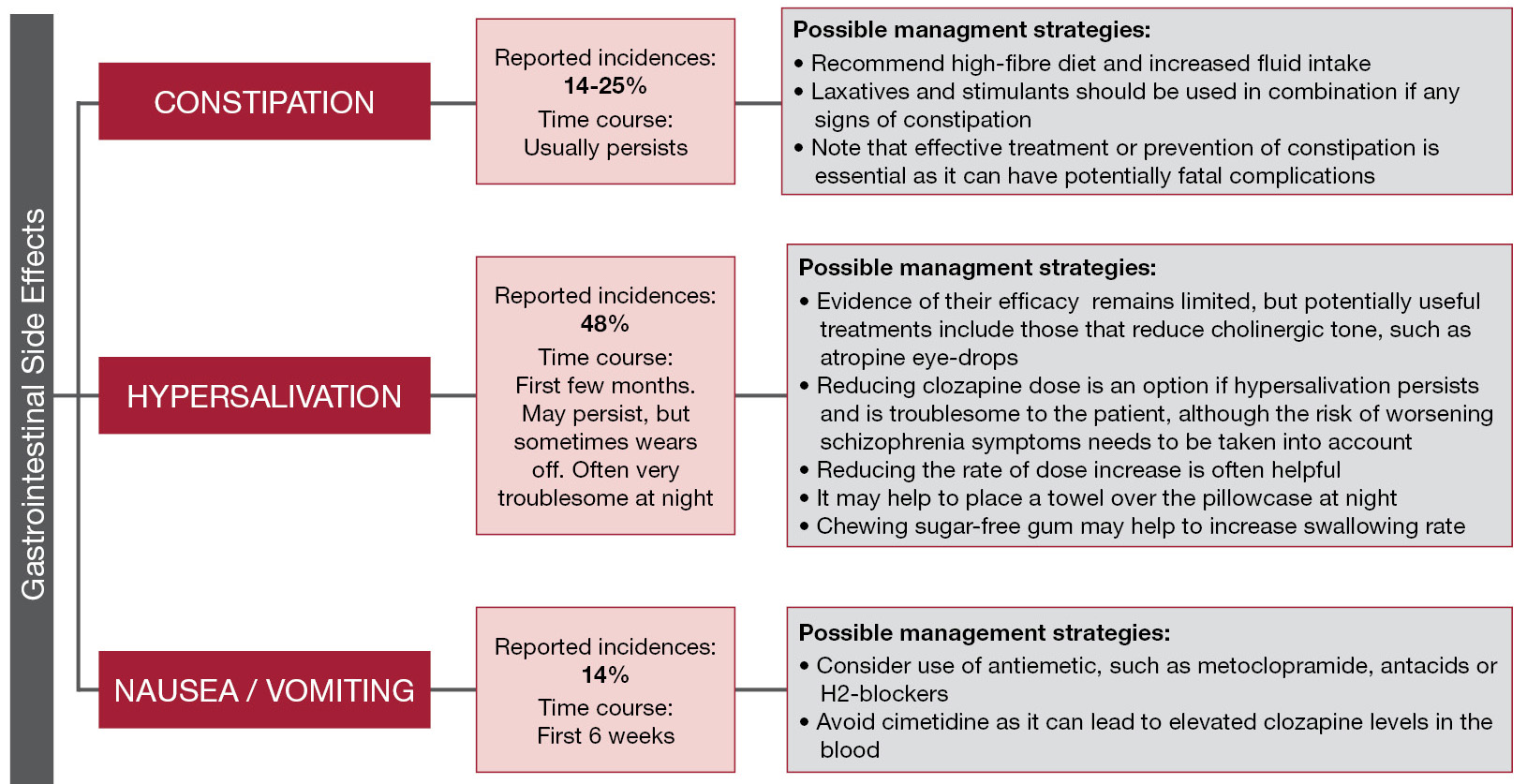

Diagram 1. Summary of gastrointestinal side effects of clozapine.

Clozapine has an extensive side effect profile, however, it is still an invaluable option for treatment–resistant schizophrenia. Diagram 1 above summarises the therapeutic alternatives for these prominent gastrointestinal side effects that tend to be overlooked. It is essential that these additional side effects are recognised and addressed to ensure patient wellbeing and to prevent unnecessary discontinuation of therapy.

References:

- Azorin JM, Spiegel R, Remington G, et al. A double–blind comparative study of clozapine and risperidone in treatment – resistant schizophrenia: a double – blind crossover study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003 23(6):668 – 671.

- Buchanan RW, Breier A, Kirkpatrick B, Ball P, Carpenter WT. Positive and negative symptom response to clozapine in schizophrenic patients with or without the deficit syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1998; 155(6): 751–60.

- Camilleri M. Serotonin in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2009; 16(1):53–9.

- Cohen D, Bogers JP, Van Dijk D, Bakker B, Schulte PF. Beyond white blood cell monitoring: screening in the initial phase of clozapine therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012; 73(10):1307-12.

- Conley RR, Kelly DI, Richardson G, et al. The efficacy of high – dose olanzapine versus clozapine in treatment – resistant schizophrenia: a meta – analaysis. Lancet 2009 373(9657):31 – 41.

- Cree A, Mir S, Fahy T. A review of the treatment options for clozapine–induced hypersalivation. Psychiatr Bull. 2001; 25:114–6.

- De Hert M, Hudyana H, Dockx L, Bernagie C, Sweers K, Tack J, et al. Second–generation antipsychotics and constipation: a review of the literature. Eur Psychiatry. 2011 26(1):34–44.

- Flanagan RJ, Ball RY. Gastrointestinal hypomotility: an under–recognised life–threatening adverse effect of clozapine. Forensic Sci Int. 2011; 206(1-3):e31–6.

- Grabowski J. Clonidine treatment of clozapine–induced hypersalivation. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992; 12(1):69–70.

- Idanpaan – Heikkila J, Alhava E, Olkinuora M, Palva IP. Agranulocytosis during treatment with clozapine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1977; 11(3):193–8.

- Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H. Clozapine for the treatment – resistant schizophrenic: a double – blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988 45(9):789–96.

- Lamba G, Ellison JM. Reducing clozapine-induced hypersalivation. Current Psychiatry 2011; 10(10): 77-8.

- Miller DD. Review and management of clozapine side effects. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000; 61(Suppl 8): 14–7.

- Mustafa FA, Khan A, Burke J, Cox M, Sherif S. Sublingual atropine for the treatment of severe and hyoscine–resistant clozapine–induced sialorrhea. Afr J Psychiatry. 2013; 16(4):242.

- Nielsen J, Correll CU, Manu P, Kane J. Termination of clozapine treatment due to medical reasons: when is it warranted and how can it be avoided? J Clin Psychiatry. 2013; 74(6):603-13.

- Nielsen J, Dahm M, Lublin H, Taylor D. Psychiatrists’ attitude towards and knowledge of clozapine treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 2010; 24(7): 965-71.

- Nielsen J, Nielsen RE, Correll CU. Predictors of clozapine response in patients with treatment–refactory schizophrenia: results from a Danish Register Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012; 32(5):678-83.

- Raja M. Clozapine safety, 35 years later. Curr Drug Safety. 2011 6:164 – 184.

- Sagy R, Weizman A, Katz N. Pharmacological and behavioural management of some often–overlooked clozapine–induced side effects. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014; 29(6):313–7.

- Syed R, Au K, Cahill C, Duggan L, He Y, Udu V, et al. Pharmacological interventions for clozapine-induced hypersalivation. Cochrane DB Syst Rev. 2008; 16(3): CD005579.

- Van Kammen DP, Marder SR. Serotonin – dopamine antagonist (atypical or second generation antipsychotics). In: Sadock BJ, Saddock VA, editors. Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. P. 2914 – 2937.

- Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM. Clozapine: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in patients with schizophrenia who are unresponsive to or intolerant of classical antipsychotic agents. CNS Drugs 1995 4:370 – 400.