Venous thromboembolism (VTE) assessment is one of the most important areas of supportive care in cancer patients. The incidence of VTE in cancer patients ranges from 4-20%, which represents a significant patient population. It is of paramount importance that healthcare professionals remain up-to-date with current VTE treatment and prophylaxis guidelines; ensuring all cancer patients are appropriately educated.

Risk Factors

Those at the highest risk of a VTE are hospital inpatients and patients who are currently receiving chemotherapy. Cancer patients are at three times the risk of VTE than that of the general population, and cancer patients receiving chemotherapy are at a sevenfold higher risk of VTE than non-cancer patients. The risk may be even higher depending on the type of cancer, the patient’s nutritional status, the response to chemotherapy and the extent of metastases. Surgery and the presence of indwelling arterial or venous catheters may also contribute to an increased overall risk.

The proposed mechanism of the increased coagulability in cancer patients is complex and involves several factors: procoagulants produced by tumour cells, platelet activation and suppression of fibrinolysis. The most significant procoagulant is tissue factor (TF), observed by Tesselaar et al. to function as a cofactor for factor VIIa, which converts factor X into factor Xa. It is worth noting that TF is a procoagulant in the extrinsic coagulation pathway, which may explain why cancer patients with VTE have better outcomes when treated with heparins, rather than with vitamin K antagonists.

A recently developed and validated predictive model may be used to assess the risk of VTE associated with chemotherapy in ambulatory cancer patients, as shown in Table 1. A total added score of 0 indicates low risk (0.5%), a score of 1-2 indicates moderate risk (2%) and a score of 3 or above indicates high risk (7%).

Table 1. VTE associated with chemotherapy in ambulatory cancer patients.

| Risk Factors | Score |

| Cancer-related risk factors | |

| Very high risk cancer site (stomach adenocarcinoma, pancreas adenocarcinoma) | 2 |

| High risk cancer site (lung, lymphoma, gynaecological, testicular, bladder) | 1 |

| Haematological risk factors | |

| Pre-chemotherapy platelet count ≥350,000/microL | 1 |

| Haemoglobin <100g/L or use of erythropoiesis stimulating agents (ESA) | 1 |

| Pre-chemotherapy leukocyte count >11,000/microL | 1 |

| Patient-related risk factor | |

| Body mass index (BMI) ≥35kg/m2 | 1 |

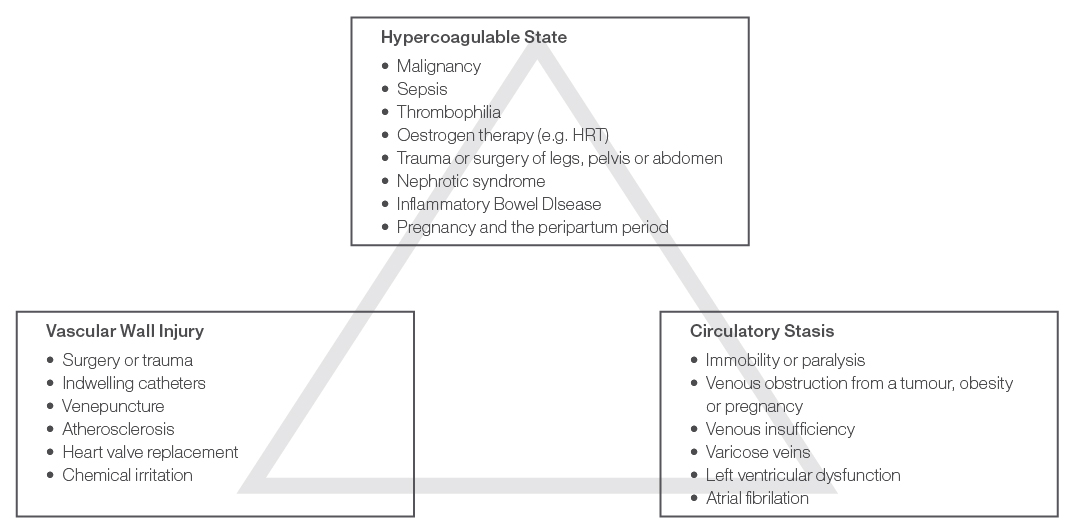

Virchow’s Triad, as shown in Figure 1, illustrates the three broad risk categories which may contribute to a VTE: hypercoagulable state, vascular wall injury and circulatory stasis. A cancer patient may be exposed to risk factors from all three of these categories, putting them at exceptionally high risk of VTE.

Figure 1. Virchow’s Triad.

Inpatient Prophylaxis

Current data is insufficient to support the routine use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in cancer patients undergoing short admissions, such as minor procedures and short chemotherapy infusions.

However, all hospitalised patients with an active malignancy should be considered for pharmacologic prophylaxis. Unless contraindicated, hospitalised patients with a malignancy, reduced mobility, or an acute medical illness should receive pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis, such as a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), unfractionated heparin (UFH) or fondaparinux.

Outpatient Prophylaxis

Thromboprophylaxis is not routinely recommended in cancer outpatients. It may be considered in high risk patients with solid tumours, but there is a lack of evidence with respect to the overall risk versus benefit, appropriate dose, or duration of treatment. Patients undergoing treatment with thalidomide or lenalidomide for multiple myeloma should receive pharmacological thromboprophylaxis; aspirin or LMWH for low risk patients and LMWH for high risk patients. The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Clinical Practice Guidelines also recommend low dose warfarin to target an INR (international normalised ratio) of 1.5.

Surgical Prophylaxis

All cancer patients undergoing a surgical intervention should be considered for thromboprophylaxis either with UFH or LMWH, unless such treatment is contraindicated. Mechanical prophylaxis, such as graduated compression stockings and intermittent pneumatic compression devices may also be used to improve the efficacy of the prophylaxis. Prophylaxis should be commenced pre-operatively and continue for at least 7-10 days. Patients who have undergone major abdominal or pelvic surgery and have additional risk factors such as reduced mobility or a personal history of VTE may be considered for prophylaxis for up to four weeks following surgery.

Treatment Options and Secondary Prophylaxis

LMWH for 5-10 days at a treatment dose is the preferred option for patients with cancer and a newly diagnosed VTE. Initial treatment should be followed by six months of LMWH at a prophylactic dose. UFH is preferred in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30mL/min). Vitamin K antagonists may be used if LMWH is unavailable, but are not as effective. Secondary prophylaxis beyond six months may be considered for some patients, particularly in those with metastatic disease and those receiving chemotherapy. A vena cava filter may be used if anticoagulation is contraindicated, or as an adjunct to anticoagulation in the event of treatment failure. At this stage, the use of novel oral anticoagulants isn’t recommended in cancer patients.

Contraindications and Precautions

There are many absolute and relative contraindications to anticoagulant therapy, all of which are related to the increased risk of bleeding. Absolute contraindications to anticoagulation therapy include: major or life threatening active bleeding, including bleeding in a critical site not reversible by a medical or surgical intervention, severe uncontrolled hypertension, an inherited bleeding disorder, major platelet dysfunction or persistent thrombocytopenia <20,000/microL and selected surgical procedures (lumbar puncture, spinal anaesthesia and epidural catheter placement).

There are also many precautions to the use of anticoagulant agent, such as non-life threatening active bleeding, a recent surgery or episode of bleeding, patients at high risk of intracranial or spinal bleeding (such as those with CNS malignancies) and thrombocytopenia <50,000/microL. Such complications should be carefully weighed up on a case-by-case basis before the decision is made to treat with an anticoagulant.

Patient Counselling

All cancer patients and their carers should receive sufficient education on the increased risk of VTE due to malignancy, early warning signs, and how to respond if they suspect they have a VTE. Nurses and pharmacists are well positioned to provide patients and carers with education. Warning signs of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) include unilateral pain, swelling and discolouration of an extremity. A pulmonary embolism (PE) may present with unexplained shortness of breath, chest pain, syncope, and rapid breathing and heart rate. Patient education should occur prior to, and on a regular basis during the patients’ treatment, to increase awareness and the likelihood of early intervention.

References:

- DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA et al. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th ed. North America: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

- Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E et al. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associted thrombosis. Blood. 2008; 111(10): 4902-4907.

- Lee A, Levine M, Baker RI et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 146–153.

- Lyman GH, Korana AA, Kuderer NM et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31(17): 2189-2205.

- Mandalà M, Falanga A, Rolia F. Management of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2011; 22 (Suppl 6:vi): 85-92.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Venous Thromboembolic Disease. V.1.2009.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Clinical practice guideline for the prevention of venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) in patients admitted to Australian hospitals. Melbourne: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2009.

- Rang HP, Dale MM, Ritter JM, Flower RJ. Rang and Dale’s Pharmacology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Limited; 2007.

- Skeel RT, Khleif SN. Handbook of Cancer Chemotherapy. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

- Tesselaar MET, Romijn FPHTM, Van Der Linden IK et al. Microparticle-associated tissue factor activity: a link between cancer and thrombosis? J Thromb Haemost 2007; 5: 520–7.